|

|

Putting peanut immunotherapy into practice |

Michelle Berriedale-Johnson visits the Cambridge Peanut Allergy Clinic to talk to Dr Andrew Clark whose ground-breaking research back in 2014 made the clinic possible – and to some of the children undergoing treatment. |

|

Why were the trial results so exciting? Big news because, until then, the only 'treatment' on offer for families trying to cope with a peanut allergy was total avoidance – and 'total' meant 'total'. Not a speck of peanut dust could be risked. This severely limited what the allergy sufferer could eat or even touch, where they could go, even what friends they could make. It dramatically impacted on the life of the whole family, creating major anxieties and often mental health problems for the child, for its parents or for its siblings. The trial results did not offer a 'cure' as such but they suggested that sufferers could acquire sufficient 'tolerance' to no longer be threatened by peanut contamination or peanut dust even though they might not be able to safely eat a peanut butter sandwich. In other words, that they could lead a 'normal' life and just avoid eating peanuts. What next? All too often studies like this generate huge excitement but, in practical terms, little changes. The route from a successful trial to a successful treatment is long, slow and beset by regulatory, financial and practical pitfalls. And we are still a very long way from the NHS offering peanut immunotherapy as a standard treatment for peanut allergy. However, the team at Addenbrookes were not content to follow the usual pattern and merely move on to more research (although they are also keen to do that). The result is the Cambridge Peanut Allergy Clinic, based at Addenbrookes, where they actually treat peanut allergic children from 7 to 16 years of age, the age group covered by the trial. (They hope in due course to extend the age range to cover younger and older children and even adults but that will require further clinical trials.) Although the service is based in, and fully supported by the hospital, it is a private clinic, and treatment is not cheap. The full course, which runs over two years, will set you back around £17,000. However, staffing levels are extremely high – three consultants, a junior doctor and 8-9 specialist nurses – for a relatively small number of patients. Over the two years that the clinic has been running they have only treated 135 children. However, there seems to be little doubt among the families who have made the investment that it has been worth every penny. 'Absolutely life changing' is the most common reaction. What does the treatment actually consist of

Dr Clark The treatment is actually incredibly simple. It consists of feeding the patient minute doses of peanut protein which, if they are well tolerated, are then gradually increased over three to four months. The purposes is to 'teach' the immune system, very gradually, that peanut protein is neither harmful nor threatening and that it does not therefore need to trigger an emergency allergic reaction to expel it from the body. However, that is where the simplicity ends. Because the reaction to peanut in a severely allergic person can be dramatic and indeed life threatening, it is vital that the initial treatments only happen under expert medical supervision using the tiniest, pharmaceutically formulated doses of the protein. This is NOT possible to achieve at home and NO ONE should be tempted to try it. This means that the treatment can only be given in a dedicated clinic, with the appropriate resuscitation skills and equipment. Funding and staffing such a clinic (given the dearth of allergy specialists and money in the NHS right now) is extremely challenging. Peanut flour must be treated as a drug... And the complications don't end there. Although the 'medication' is actually a food – the peanut protein in peanut flour – it is required to be licensed as a drug. This means that before it could be recommended for treatment by NICE, it has to go through the full 3–5 year drug testing protocol (phase 1 on healthy volunteers; phase 2 on patients to assess efficacy and side effects; phase 3 on patients to assess efficacy, effectiveness and safety) with all of the costs and red tape associated with such trials. For now the clinic is permitted to use a specially formulated peanut flour which can only be supplied 'on a named patient basis to individual patients who have clinical needs that cannot be met by licensed medicinal products'. Dr Clark and Dr Ewan have meanwhile set up CamAllergy and are raising investment to fund trials of the 'flour-drug'. But they are 3-5 years away from completing those trails. At that point they can apply to NICE to have the treatment rolled out. But they could lose out to an American company, Aimmune Therapeutics, who are developing a similar 'oral biological drug', as Aimmune Therapeutics are a couple of years further along the trial process than CamAllergy. Even assuming that the trials all go well and that either CamAllergy or Aimmune Therapeutics get their peanut flour capsules licensed, they then have to persuade NICE to set up guidelines for their use. Once they have done that, peanut immunotherapy becomes a licensed 're-inbursable' treatment. But they then have to persuade other allergy clinics to actually undertake the treatment with the investment in staff and equipment that it requires. So while it is wonderful to know that a successful treatment for peanut allergy now exists, the chances of it appearing in a hospital near you anytime soon are not great! And.... if it works for peanuts, can it work for other allergens? In theory, says Dr Clark, yes. But.... There would need to be full independent testing for each allergen, as each treatment would be 'a discrete pharmaceutical product'. So how does the treatment actually work?

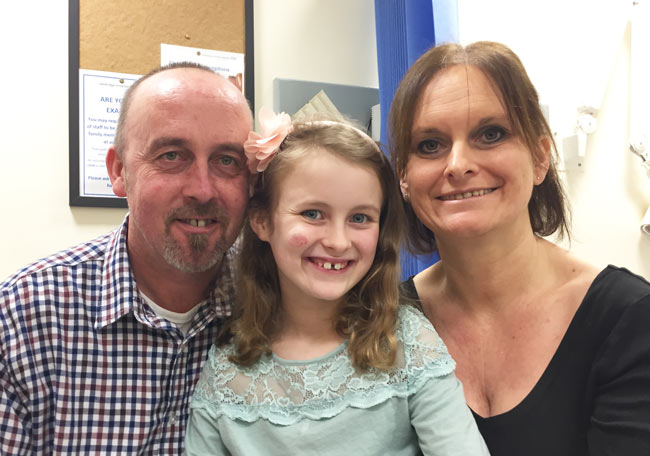

Assuming that he or she is accepted, then they start a 14 week programme, visiting the clinic in Cambridge every two weeks. This can involve quite a long journey for many of the patients often necessitating an overnight stay, all of which can add to the cost. On each visit they will be given the appropriate dose of peanut protein (starting at 2mg and working up to 200 mg – effectively 2 peanuts) in a pot of yogurt. The child will then be carefully monitored for two hours to ensure that there are no reactions. Assuming that there are not, the child will go home and continue to take that dose of peanut protein in yogurt each day for the next two weeks before returning to the clinic 14 days later to have the dose increased. However, although this sounds very simple, it is crucial that they remain quiet for a two hour period every day after the ingestion of their dose of peanut protein, not just for the 14 weeks of the treatment at the clinic but for the remaining 90 weeks of the two year programme. Moreover, they very specifically must not take their dose late at night (so that they are fully awake for the full monitoring period). This discipline may become increasingly irksome the further into the programme the child gets, especially if the treatment appears to be working and they have not had any reactions. Meanwhile, they will return to the clinic for follow up consulations at the end of 12 months and at the end of the two years. Assuming that they do make it through to the end and are tolerating the two peanuts a day which is the target 'dose' then they no longer have to take a daily dose or rest afterwards, but they do have to make sure that they take 200mg of peanut protein weekly, indefinitely, to maintain their tolerance. From the patients' perspective On the day I went to Cambridge, Ella, aged 8, who is allergic to peanuts and to treenuts, was there with her mum Caroline and her dad, Doug, for her first treatment. Here they are...

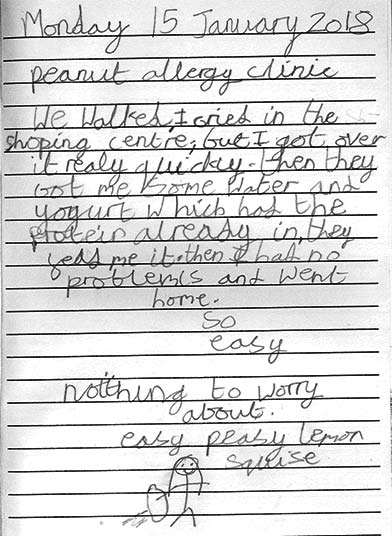

Ella had already had her dose of peanuts protein when I met her and was being monitored. Now that it had happened she was very chirpy, but admitted that she had been quite scared before hand: 'I was scared and cried before going in but got over it quickly. It was a little scary, then after I had the Nutlife I said ‘I don’t know what I was worrying about, that was fine.’ And this was what she wrote in her diary when she got home:

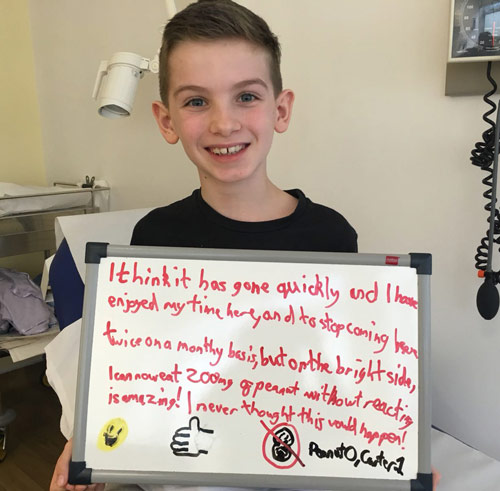

It sounded as though the shopping centre nearby could be a major incentive for Ella to turn up every second week! However, the most exciting benefit of the treatment for her was that she would be able to eat in restaurants with her friends. I asked Ella whether she realised that she was going to have to sit quiet for two hours after her treatment every day for the next two years and whether it was worth it – '100%' was the answer. What was she going to do? 'Watch YouTube on my tablet, and do craft and talk to mum and dad.' As far as mum and dad, Caroline and Doug, were concerned, the immediate benefits in terms of not having to check so rigorously on everything that Ella ate, being able or travel and go to restaurants were obviously very appealing. But the real driver behind their investment was the future – when she was into her teens, was no longer under their control and might (very likely would) become less careful about what she ate and drank. Reducing her risk at that point was what they were really desperate to do. As they said, what were a few missed holidays or extra luxuries when compared with the possibility that, without this 'induction of tolerance' she might one day have fatal reaction? Ella had been very lucky. All of her family, her friends and her school are very understanding and supportive of her allergy so she had not really had any bad experiences. Unfortunately, according to Dr Clark, this is absolutely not always the case and a number of their children had been bullied, had food thrown at them or been excluded from friendship groups. For ten year old Carter (see here with dad, Paul) and his family, the long term benefits of the treatment were also the most important.

Carter had also been very lucky in that his school is nut free school and both his teachers and his friends are very understanding and supportive of his peanut allergy. Carter also has a younger sister who is a 'very fussy eater' so food restrictions are a common issue around the house. But for Paul and Kerry, his mum and dad, it was less the current restrictions that they were concerned about – indeed they had managed pretty well up till now, had travelled and had even taken Carter on safari. What concerned them was the future, the risks which they could foresee when he was no longer under their care as a teenager and then as a student, subject to all the temptations and risks that surround any allergic teenager or student when they first leave home. Securing him from those was worth almost any investment. For Carter, as for Ella, the most immediate benefit of the treatment was being able to eat out with his friends – as is very obvious from this video that he recorded for us with Paul! Carter has now successfully completed his first 14 weeks so is now on his own for the next 21 months – but he has promised us a regular video diary charting his progress. And here he is – finished at the clinic for now – although he has the rest of his two years to complete – and able to eat two whole peanuts!!!

Cole and Julia To read Cole's story - he has just had his one-year check up - check in to the CamAllergy site here. His mum, Julia says: 'Cole has become a different young man. He is more confident, less stressed and visibly walks taller. He enjoys taking trips into town with his mates, he’s now enjoying going on school trips and takes the school bus. Best of all, Cole does not feel different to any of his friends. What to do if you are interested in the course The Cambridge Peanut Allergy Service website will provide you with the basic information, a contact form and contact details and that is where to start. They will guide you through from there. You do not require a referral from your GP, although the service will keep them informed if you go on to take the course. There is currently no funding available that you can tap into. Dr Clark says that there is a hospital-based charity that they approached and who were keen, but that the initiative stalled when a solution to mean-testing could not be found. February 2018 If you found this article interesting, you will find many more articles on peanut and tree-nut allergy here, and reports of research into the conditions here. |

Just over four years ago the allergy world was sent into a flurry of excitement by the

Just over four years ago the allergy world was sent into a flurry of excitement by the  To find out how it works, I spent a morning at the clinic talking to Dr Andy Clark about the treatment – and to two children and their parents about the why they decided to invest so much money with CamAllergy and how it was going for them. Emma, aged 8, was having her first treatment, and Carter, aged 10, was half way through his course. See below for Emma's 'interview' and diary and for a video that Carter made with his dad.

To find out how it works, I spent a morning at the clinic talking to Dr Andy Clark about the treatment – and to two children and their parents about the why they decided to invest so much money with CamAllergy and how it was going for them. Emma, aged 8, was having her first treatment, and Carter, aged 10, was half way through his course. See below for Emma's 'interview' and diary and for a video that Carter made with his dad. The treatment starts with an initial assessment at the clinic to ensure that the child is suitable for the treatment. This could depend, among other issues, on the severity of the allergy or whether the child has other allergies or health issues such as asthma.

The treatment starts with an initial assessment at the clinic to ensure that the child is suitable for the treatment. This could depend, among other issues, on the severity of the allergy or whether the child has other allergies or health issues such as asthma.