|

|

|

Allergy-Free Kids Can food allergy be prevented in children? Alex Gazzola considers the recent evidence, and reviews a new book, inspired by the LEAP and EAT studies, aimed at parents hoping to do just that. |

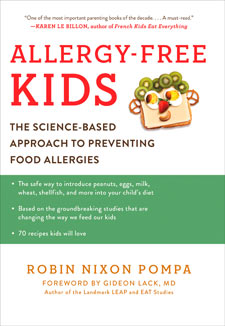

“Feed kids allergens, early and often”. Six words, forming a straightforward piece of advice which summarises the core message behind this new book by science journalist and mother Robin Nixon Pompa. The recommendation itself is drawn from several extraordinary recent studies, and it could have huge ramifications for many years to come – if it can be communicated widely and clearly enough. And while the title of the book may sound like a pipe dream, there’s no reason not to believe that the steady increase in food allergy prevalence among the young in recent decades can finally take a downward turn. It is tempting, then, to peer decades into the future and imagine such a success. The benefits are obvious – but will the picture be completely rosy? What if we become so successful at food allergy prevention in our children that those few for whom the guidance fails become an obscure medical rarity once again? Will those kids suffer far more than allergy kids of today? There is some safety in numbers, after all, even if only due to wider awareness. Will widespread scepticism return (“Oh food allergy doesn’t exist any more, does it?”), and will those manufacturers catering so well for the allergy market largely disappear – leaving the food sensitive shopper stranded back in the 20th century? I guess we will cross that bridge, if and when … Back to the book. Subtitled The Science-Based Approach to Preventing Food Allergies, it is inspired by that remarkable recent research spearheaded by King’s College London’s Professor of Paediatric Allergy, Dr Gideon Lack, whose foreword introduces us to Allergy-Free Kids. It was this work which turned long-standing allergy-prevention advice – rooted in a dogma of avoidance – completely on its head. First came LEAP – Learning Early About Peanut allergy – which randomised high-risk children into peanut-consumption and peanut-avoidance groups, and which found that early introduction of peanut protein reduced the prevalence of peanut allergy by 80%. The subsequent LEAP-On study demonstrated that such tolerance is typically maintained, even after periods of peanut abstinence. A second study, EAT – Enquiring About Tolerance – focused on the wider population, and found that introducing key allergens (peanut, wheat, egg, dairy, sesame and fish) into the diets of healthy breast-fed infants, from the age of three months, and maintaining that consumption regularly and strictly, was associated with a two-thirds reduction in food allergy incidence. The stated aim of Nixon Pompa’s book is to help parents overcome the inevitable problems of getting all those allergenic foods into their offspring’s bellies during the probable ideal window of opportunity – said to be most widely open at around four or five months, but which may only remain at best ajar until the age of five at the latest. While there are warnings to check with your allergist if your child already has food allergies or eczema, or a family history of food allergies, the underlying thinking here is that there is no reason for other infants to avoid allergens beyond six months. The book feels safe and reassuring. Under Dr Lack’s guidance, Nixon Pompa effectively cured her daughter’s egg allergy by feeding her minuscule quantities, and likewise her allergy to some tree nuts by feeding her alternative tree nuts which SPTs had previously indicated she could tolerate. It’s important to remind ourselves that anaphylaxis is extremely rare in very young children – not one case was recorded during EAT – though that does not mean the road to allergy prevention or even ‘desensitisation’ will be a smooth one. The theories behind the increase in allergies are examined in Chapter 1 – vitamin D, the hygiene hypothesis, maternal diet and lifestyle are considered, for instance – while Chapter 2 takes a more in-depth look at LEAP and EAT. Chapter 3 introduces the reader to implementation strategies for various stages of growth – including the tricky toddler years – while Chapter 4 expands on the ideas and considers allergens individually, with recommendations to aim for a minimum of 2g of each food allergen protein weekly to start with. This does lead to some very specific guidelines – 44 sticks of spaghetti, for instance – which might put some readers off. There are a fair few numbers, weights and measurements to negotiate. Nobody said it would be easy … The bulk of the book is recipes, and they constitute an eye-opening array of allergen-rich concoctions – the polar opposite of the usual creative GF, DF and NF delights anyone living or working in the field of allergy might be accustomed to. Nutty Noodles (p141), for instance, boasts wheat, soya, peanut, tree nuts, fish, sesame and eggs – but no sniff of a vegetable – and looks like the sort of dish a protein-hungry bodybuilder might hanker for. I expect the book will require fine-tuning and revision as more detailed research reveals further advice for specific allergens, and perhaps more tailored recommendations on timing of introduction and quantities. But as an attempt to translate the current science into a can-do guide for parents, the book easily succeeds. Allergy-Free Kids: The Science-Based Approach to Preventing Food Allergies, by Robin Nixon Pompa available from Amazon Useful Links Other studies include STEP (Starting Time for Egg Protein) and BEAT (Beating Egg Allergy Trial). To find out more about them, click here. Although the Food Standards Agency is believed to be still finalising their infant feeding and allergy prevention guidelines, the results of the LEAP and EAT studies have already influenced guidance from other international allergy and health associations and groups: NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) have published peanut-prevention guidelines, including a Summary for Clinicians, and guides for parents and caregivers. Find them all here. ASCIA (Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy) published a number of documents in 2016 and 2017, including Infant Feeding and Allergy Prevention, Allergy Prevention Infants FAQs, and How to Introduce Solid Foods to Infants. Find them all in their collected Allergy Prevention guidance here. ESPGHAN’s Committee on Nutrition’s Complementary Feeding position paper can be seen here (abstract only).

More articles on the management of allergy in children

|