|

|

Interpreting statistics - absolute and relative risk When you read a research report that tells you that a new drug has reduced the risk of suffering from (or increased the chances of recovering from) such and such a condition by 50%, do you really understand what that means? Michelle Berriedale-Johnson offers a brief primer – and a warning. |

|

The Guild of Health Writers recently ran a useful seminar for its members on statistics – headed up by medical journalist John Illman (author of, among other books, Handling the media: communication and presentation skills for healthcare professionals) and Dr Jennifer Rogers, Royal Statistical Society’s Vice President for External Affairs. They made a number interesting points, a few of which are logged below, but the most crucial of which related to how results of medical trials are reported. How often have you read of a new treatment which has increased the survival rates for a certain condition by 50% – and thought – 'How amazing, what a brilliant drug. I do hope the NICE clears it for use.' But does that 50% mean that half of the people who take that drug will actually be 'cured' or survive? That entirely depends on how the figures have been presented and whether that 50% is a 'relative' or an 'absolute' figure. Absolute and relative risk Statistics are a complicated business and it is very easy to get bogged down in technical terminology: assumed risk, baseline risk, odds ratios, standardised mean difference, dichotomous outcomes etc etc. But the basic principles underlying relative and absolute risk are actually very simple. For a clear explanation see this page from the American College of Physicians, but for a potted version see below. Consider the risk of blindness for diabetic patients.

This describes the 'absolute' difference between the two therapies.

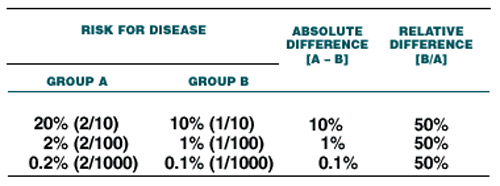

This is the 'relative' difference between the two therapies. Both figures are correct but they tell a very different story. And for obvious reasons, purveyors of new treatments, be they drugs or other, wanting their product to be seen in the most favourable light, will all too often quote the relative difference without reference to the absolute difference. But this can give a totally false picture of the efficacy of their product. The apparent risk or efficacy can become even further distorted if the numbers of those involved in the research are not quoted either. The table below, copied from the excellent ACP page quoted above, illustrates this extremely well by comparing the results when only two people are affected but they are part of a group of 10, of 100 or of 1000 subjects. The relative difference remains the same; the absolute difference (or the number of people actually affected) plummets from 10% to 0.1% of the group.

Controls? Given the enormous possible disparity between the figure for absolute and relative risk it would be reasonable to assume that there were some sort of controls in place which would require the purveyors of both drugs and therapies to quote both figures – and to give some indication of the numbers of people involved in the trials. But there are not. And while you or I might think that this suggests that we are being deliberately misled, the purveyors of those drugs and therapies will claim that relative figures are perfectly valid figures. Which they are, but only in context. All too often that context is not given. So, when reading those super up-beat reports on the most recent drug trials, be warned. They may not be as positive as they seem. A couple of other points to bear in mind Numbers Aside from the issue of absolute and relative differences, numbers of participants in any given piece of research are also relevant is assessing the outcome and population benefit. A 1% change in a group of 1000 people will mean that 100 people have experienced that change; a 20% change in a group of 10 people means that only 2 people will have experienced it. Moreover a small number will not allow researachers to get a broad enough picture of the group, so while trials with very small numbers may be of interest, they too should be treated with caution. Correlation is not causation The fact that two things happen at the same time does not necessarily mean that one has caused the other.

Or, in an area closer to allergy.

Again treat such theories with caution until all relevant information hs been assessed and controlled for. Meanwhile, many thanks to the Guild of Health Writers for putting on such a useful event – and, those of you studying research reports – do not believe everything you read. June 2017 • If this article was of interest you will find many other articles on unlikely allergies and allergy connections here – and links to many relevant research studies here. |